Roger Fisher and William Ury (Harvard PON) tell the story of two sisters arguing over an orange. After some discussion they agree to divide the orange in half, an apparently wise and fair solution. One sister then peels her half and eats the fruit, while the other peels her half, throws away the fruit and uses the peel to bake a cake.

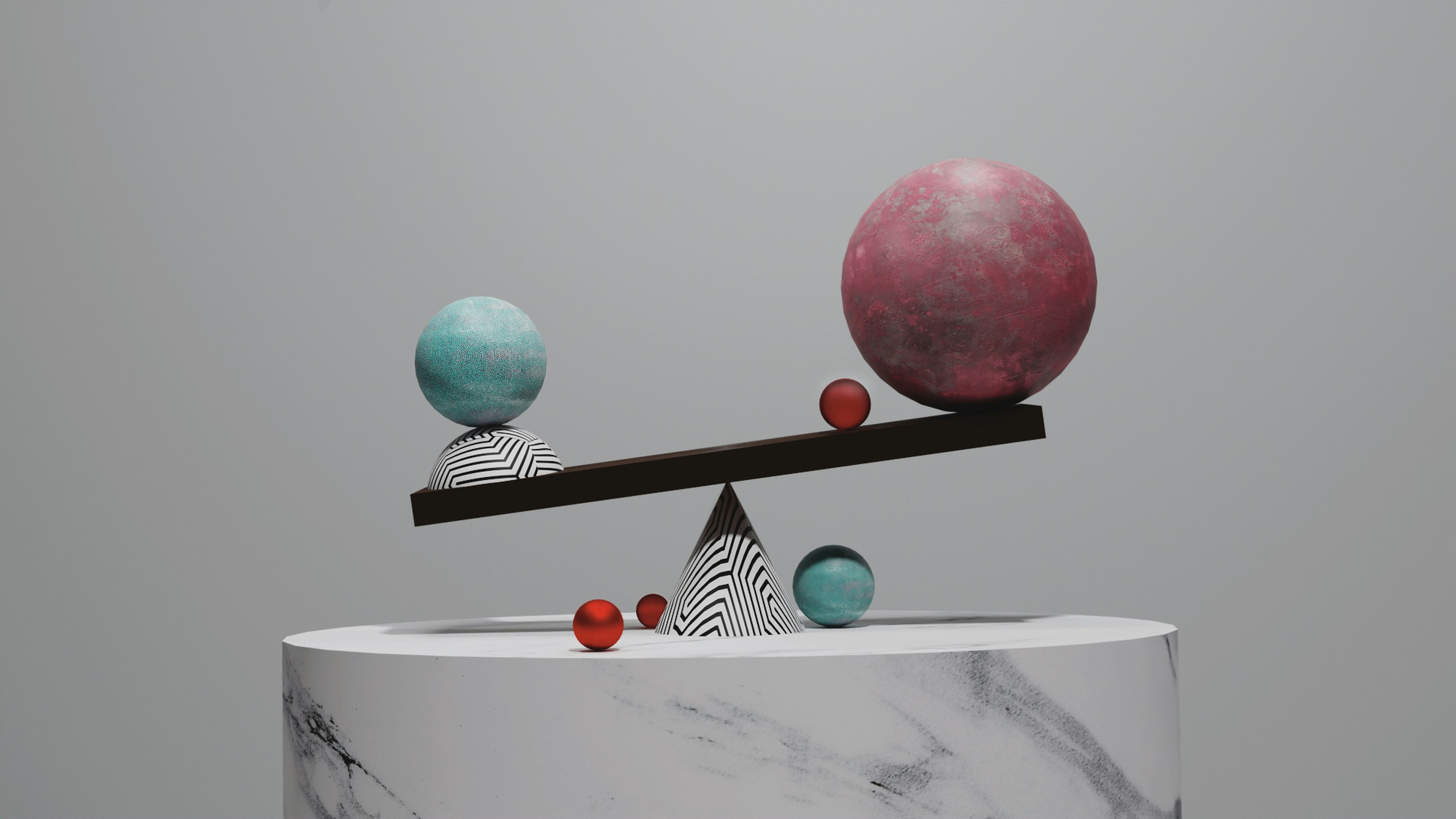

What appeared to be a wise solution namely a 50-50 division of the orange was certainly fair, but not very wise. If only the sisters had paid less attention to their positions (how much of the orange each was asking for) and move to their interests (why each of them wanted the orange) they could have reached an agreement which allowed both to obtain everything they wanted.

Instead of analysing negotiation as a confrontation between two adversaries (each of whom is determined to get as much as possible while surrendering little or nothing along the way), the 'Principles of Problem-Solving' approach calls for greater collaboration. Each side seeks to do well as possible for itself, but views the other party not as an adversary but as a potential collaborator. The objective is to find ways to advance one's self interest while also leaving room for the other side to do the same. This calls for negotiators to move from statements of position to an analysis of underlying interests.

Exponents of this approach to negotiations argue that opportunities for joint gain result when negotiators are able to metaphorically swing their chairs round so that, instead of facing each other, they are side by side - instead of confronting each other, they jointly confront a problem that challenges both.

People negotiate with one another all the time - wives with husbands, managers with workers, nations with other nations. Yet despite the fact that it is a part of everyday life, the ability to study negotiation systematically is still neglected. To be sure, not all conflicts are amenable to this joint problem-solving approach, many are, however. Others remain better suited to the more traditional concession-making process, alluded to earlier, in which the negotiators begin with extreme opening demands, then slowly shift from these in order to reach some sort of mutually acceptable agreement.

Although these two methods of thinking about negotiation would appear to rest on rather different assumptions about the nature of the process, they are actually very alike in one key aspect. Both points of view are best suited to the kind of negotiation that takes place between parties of equal power. Whether it is two sisters, or two super-powers, as long as neither party has the power to impose agreement on the other, and parties acknowledge their interdependence, there is room and opportunity for negotiation.

But what happens when power is not equally divided between the parties - when one side has far more power than the other, when one side is far less dependent on reaching a negotiated settlement than the other? As Jeff Rubin and Jeswald Salacuse (Harvard PON) point out, If two nations are engaged in a water rights dispute concerning a river, and one nation sits upstream of the other, why should the upstream party agree to negotiate - rather than simply decide unilaterally to do exactly as it pleases. In turn, what can the party with low relative power do to persuade its upstream counterpart to come to the negotiating table.

It is usually assumed that success in negotiations is merely a matter of power and that the company with less power is always at the mercy of the company with more power. Yet the history of international relations is filled with examples of large states which failed to force small states to do their bidding (E.g. The US and Vietnam, the USSR and Afghanistan). These examples raise the question whether results in such negotiations are not just a matter of power, but also of strategies and tactics.

It is said that everyone loves an underdog, that the skilled negotiator should be able to turn this phenomenon to his of her advantage, that often the seemingly weak are far more powerful than they realise, and that the powerful may be far weaker than is commonly supposed. Well, no method can guarantee success if all leverage lies on the other side. The most any method of negotiation can do is to meet two objectives: to protect you against making an agreement you should reject and to help you make the most of the assets you do have so that any agreement satisfies your interests as well as possible.

So is there a measure for agreements that will help you achieve these aims? Yes there is - develop your BATNA (best alternative to a negotiated agreement). The relative negotiating power of parties depends primarily upon how attractive to each is the option of not reaching an agreement. Generating BATNAs requires three distinct operations.

- Inventing a list of actions you might conceivably take if no agreement is reached.

- Improving some of the more promising ideas and constructing them into practical alternatives.

- Selecting tentatively the one option that seems best.

Having gone through this effort, you now have a BATNA. Judge every offer against it. Having a good BATNA can help you negotiate on the merits. Apply knowledge, time, money, people, connections and wits into devising the best solution for you, independent of the other side's assent.